Presented by: Chrysa Koutsiouki, MD

Edited by: Penelope de Politis, MD

A 43-year-old woman presented with subacute painless visual loss in the left eye.

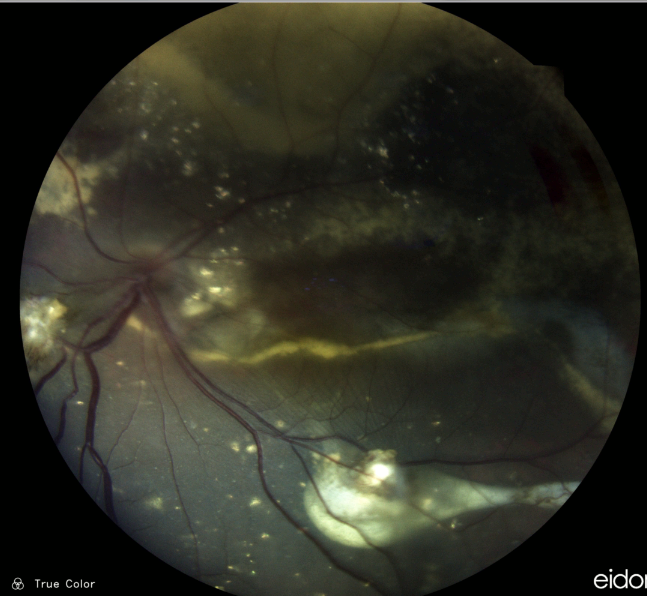

Figure 1: Color photograph of the left eye posterior pole showing macular edema, hard exudates in a circinate pattern and in plaques, and inferior retinal folds resulting from exudative retinal detachment, with anterior displacement of the retinal vessels.

Case History

A 43-year-old Caucasian woman was referred for investigation of decreased vision in the left eye (LE) noticed by chance 1 week prior to the visit while self-occluding the right eye (RE). The patient suffered from mixed anxiety-depressive disorder (MADD) diagnosed 2 years before and was currently in use of venlafaxine and bromazepam. Her past ocular history was unremarkable. Her family medical history was negative for ophthalmic diseases. Her corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA) was 10/10 in the RE and limited to light perception (LP) in the LE. Refractometry without cycloplegia was -0.25 in the RE and plano in the LE. A relative afferent pupillary defect was present on the left with a relatively fixed pupil. Biomicroscopy revealed posterior synechiae in the LE — extending from 3 to 7 o’clock — with no evidence of anterior chamber reaction (cells, keratic precipitates, flare), nor iris nodules or transillumination defects. Intraocular pressure (IOP) was within the normal range in both eyes. Fundus examination of the LE showed massive exudation in all 4 quadrants, in the form of hard-exudate plaques and circinate deposits, exudative retinal detachment along the inferior arcade extending to the inferior quadrant, and dilation and angulation of the retinal veins (Figure 1). Findings in the RE were limited to mild macular retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) changes (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Confocal high-resolution widefield imaging of the right eye (iCare EIDON®).

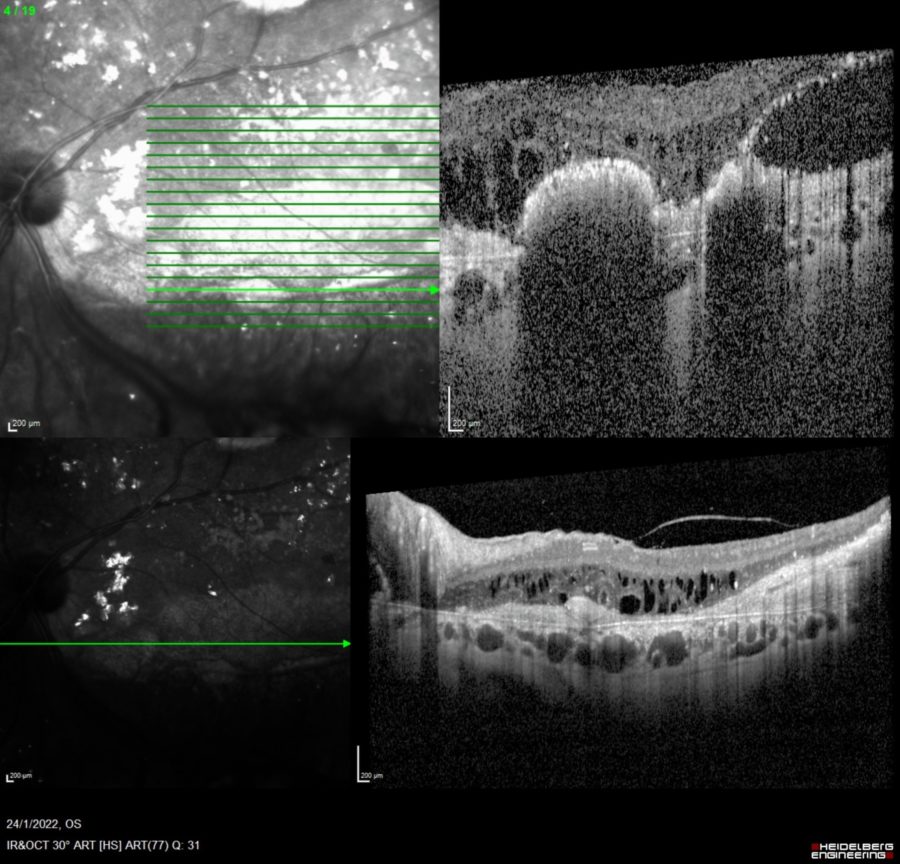

Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) displayed retinal thickening and extensive parafoveal neurosensory detachment inferior to the macula in the LE, secondary to exudative detachment (Figure 3). A small, shallow perifoveal pigment epithelium detachment (PED) was detected in the RE.

Figure 3: Spectralis SD-OCT (Heidelberg Engineering®) of the LE displaying the parafoveal neurosensory detachment extending to the optic disc. Diffuse retinal thickening, cystoid macular oedema (CMO), hyper-reflective material and outer retina atrophic changes are noticeable.

Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) was normal in the RE. In the LE there was early leakage at the macula and periphery resulting from the telangiectatic changes, followed by late diffuse leakage (Figure 4).

Figure 4: FFA of the LE (Heidelberg Engineering®). Early frame (right): inferior exudative detachment with the demarcation line noticed as hypofluorescence caused by the retinal fold masking. Late frame (left): diffuse leakage.

Indocyanine-green angiography (ICG-A) was normal in the RE. In the LE, telangiectatic changes were noticed in the early frames, along the area of the inferiorly located exudative detachment (Figure 5).

Figure 5: ICG-A of the LE (Heidelberg Engineering®). Early frame (right): evidence of telangiectatic changes. Late frame (left): telangiectatic vessels at the area of the exudative detachment.

Additional History

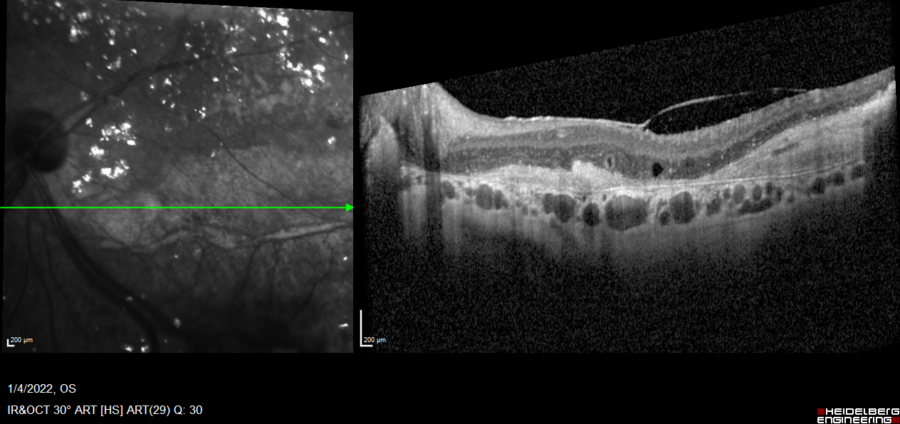

A full systemic laboratory workup aiming at inflammatory disorders was requested, and the therapy options were discussed with the patient. Intravitreal anti-VEGF and/or dexamethasone implant were proposed for the LE. Upon return 4 weeks later, all laboratory results were normal — full blood count (FBC), liver function test (LFT), urea and electrolytes (U&E) — or negative — antinuclear antibodies (ANA), antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies (ANCA), anti-DNA, QuantiFERON-TB (QFT), venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) and fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test. The clinical picture was stable. Based on the ophthalmological findings, in the absence of correlated systemic conditions, a diagnosis of adult-onset Coats’ disease with significant macular edema, exudative retinal detachment and posterior peripheral synechiae was established. The patient consented to the dexamethasone implant therapy (Ozurdex®) despite guarded prognosis given the longstanding macular edema. The intravitreal implant was injected, and the patient was given a follow-up visit in 2 weeks’ time for IOP check and at 6 weeks for assessment of treatment response. IOP remained within normal limits and vision improved from LP to hand movement (HM), with reduction of retinal thickening on the follow-up SD-OCT (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Spectralis SD-OCT (Heidelberg Engineering®) at 6 weeks post-Ozurdex implantation, showing significant improvement with complete resolution of the cystoid macular edema. Hyper-reflective material corresponding to the hard-exudate plaque and evidence of retinal atrophy can be observed.

Differential Diagnosis of Adult-onset Coats’ Disease

- IRVAN (idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms and neuroretinitis)

- sarcoidosis

- tuberculosis

- vasoproliferative tumors (e.g. retinal capillary hemangioma)

- Eales’ disease

- sickle-cell retinopathy

- lipidemia retinalis (familial hypercholesterolemia)

- toxocariasis

- age-related macular degeneration

- diabetes

- hypertension

- retinoblastoma

Because adult-onset Coats’ disease is a rare entity, diagnostic distinction must be made with more common conditions. The occurrence of retinal telangiectasis and exudation in adults, female patients, or bilaterally should prompt a search for non-Coats causes. Furthermore, a Coats’-like response may occur in patients with ocular inflammation, infection, retinal degeneration, and post radiation therapy. History and clinical presentation help differentiate such patients from the idiopathic form of retinal exudation with telangiectasia that characterizes Coats’ disease.

Discussion and Literature

Coats’ disease is an idiopathic, sporadic (non-hereditary) condition first described by Coats in 1908 as a retinal telangiectatic and aneurysmal disease associated with retinal exudation. Also referred to as idiopathic peripheral retinal telangiectasia (IPT), it typically presents in young male boys, usually younger than five years of age. More than 75% of patients are male, and 95% of cases are unilateral. There is no clear racial predilection.

The complete pathogenesis remains unclear but involves breaking of the blood-retinal barrier increasing vascular permeability and presence of abnormal pericytes leading to weakness of the vascular wall. There have been reports of localized mutations in proteins controlling retinal angiogenesis.

Coats’ disease diagnosed in adulthood is an exudative retinopathy with different features from the childhood disorder. Vascular abnormalities are often present both peripherally and juxtamacular. Adults more commonly demonstrate localized lipid deposition and hemorrhage around macroaneurysms. Milder forms are more frequent, with slower disease progression, though loss of follow-up and lack of treatment may result in irreversible vision decline.

Clinical presentation in Coats’ disease varies. Some patients may remain asymptomatic and be diagnosed by chance. Decreased vision is the most common presenting complaint. Some patients notice a defect in the visual field. Anterior segment signs such as those of uveitis may be present in advanced cases. Leukocoria is another possible finding and must push the differential diagnosis to diseases of higher morbimortality.

Coats’ disease can be classified and staged using the Shields method (following the 2000 Proctor Lecture): Stage 1, retinal telangiectasia only; Stage 2, combined with retinal exudation (stage 2A, extrafoveal exudation; 3A2 foveal exudation); Stage 3, exudative retinal detachment (stage 3A, subtotal detachment; 3A1, extrafoveal only; 3A2 foveal detachment); stage 3B, total retinal detachment; Stage 4: total retinal detachment and glaucoma; Stage 5, advanced end-stage disease.

Vascular abnormalities in fellow eyes of patients with Coats’ disease have been described, but may be asymptomatic and not necessarily progress over time. While observation is a reasonable initial management strategy, modern multimodal imaging allows the detection of even subtle vascular changes.

Due to the rarity of the diagnosis in adulthood, treatment protocols and clinical courses have not been clearly defined. The treatment regimen must be case-tailored, considering disease presentation, staging and outcomes. Combinations of intravitreal anti-VEGF, retinal photocoagulation and cryotherapy are the current mainstays. Intravitreal corticosteroids have been used to address macular edema and subretinal fluid. Epiretinal membrane and macular hole are possible long-term complications and must be managed accordingly.

Keep in mind

- Coats’ disease is mainly a vascular retinopathy of young boys. Presentation in adulthood features less extensive involvement, more benign natural course, and more favorable treatment outcomes.

- Even in unilateral cases, the bilateral nature of the disease emphasizes the need for regular follow-up to detect a possible future involvement of the fellow eye.

- Management of adult-onset Coats’ disease is case-based, considering the extension of involvement, disease staging, and response to treatment modalities.

References

- Mandura RA & Alqahtani AS (2021). Coats’ Disease Diagnosed During Adulthood. Cureus, 13(7), e16303. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.16303

- Gawęcki M (2021). Idiopathic Peripheral Retinal Telangiectasia in Adults: A Case Series and Literature Review. Journal of clinical medicine, 10(8), 1767. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10081767

- Ashkenazy N, Acon D, Kalavar M & Berrocal AM (2021). Optical coherence tomography angiography and multimodal imaging in the management of Coats’ disease. American journal of ophthalmology case reports, 23, 101177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajoc.2021.101177

- Brockmann C, Löwen J, Schönfeld S, Rossel-Zemkouo M, Seibel I, Winterhalter S, Müller B & Joussen AM (2021). Vascular findings in primarily affected and fellow eyes of middle-aged patients with Coats’ disease using multimodal imaging. The British journal of ophthalmology, 105(10), 1444–1453. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-317101

- Sen M, Shields CL, Honavar SG & Shields JA (2019). Coats disease: An overview of classification, management and outcomes. Indian journal of ophthalmology, 67(6), 763–771. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.IJO_841_19

- Kumar K, Raj P, Chandnani N & Agarwal A (2019). Intravitreal dexamethasone implant with retinal photocoagulation for adult-onset Coats’ disease. International ophthalmology, 39(2), 465–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-018-0827-0

- Jeng-Miller KW, Soomro T, Scott NL, Rao P, Marlow E, Chang EY et al. (2019). Longitudinal Examination of Fellow-Eye Vascular Anomalies in Coats’ Disease With Widefield Fluorescein Angiography: A Multicenter Study. Ophthalmic surgery, lasers & imaging retina, 50(4), 221–227. https://doi.org/10.3928/23258160-20190401-04

- Sakurada Y, Freund KB & Yannuzzi LA (2018). Multimodal Imaging in Adult-Onset Coats’ Disease. Ophthalmology, 125(4), 485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.12.007

- Li S, Deng G, Liu J, Ma Y & Lu H (2017). The effects of a treatment combination of anti-VEGF injections, laser coagulation and cryotherapy on patients with type 3 Coat’s disease. BMC ophthalmology, 17(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-017-0469-4

- Kumar P & Kumar V (2017). Vitrectomy for epiretinal membrane in adult-onset Coats’ disease. Indian journal of ophthalmology, 65(10), 1046–1048. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.IJO_322_17

- Rishi E, Rishi P, Appukuttan B, Uparkar M, Sharma T & Gopal L (2016). Coats’ disease of adult-onset in 48 eyes. Indian journal of ophthalmology, 64(7), 518–523. https://doi.org/10.4103/0301-4738.190141

- Grosso A, Pellegrini M, Cereda MG, Panico C, Staurenghi G & Sigler EJ (2015). Pearls and pitfalls in diagnosis and management of Coats’ disease. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa.), 35(4), 614–623. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000000485

- Otani T, Yasuda K, Aizawa N, Sakai F, Nakazawa T & Shimura M (2011). Over 10 years follow-up of Coats’ disease in adulthood. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.), 5, 1729–1732. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S27938