Presented by: Paris Tranos MD, PhD, FRCS, ICOphth

Edited by: Penelope de Politis, MD

A 72-year-old man was referred for intermittent unilateral blurry vision for several months.

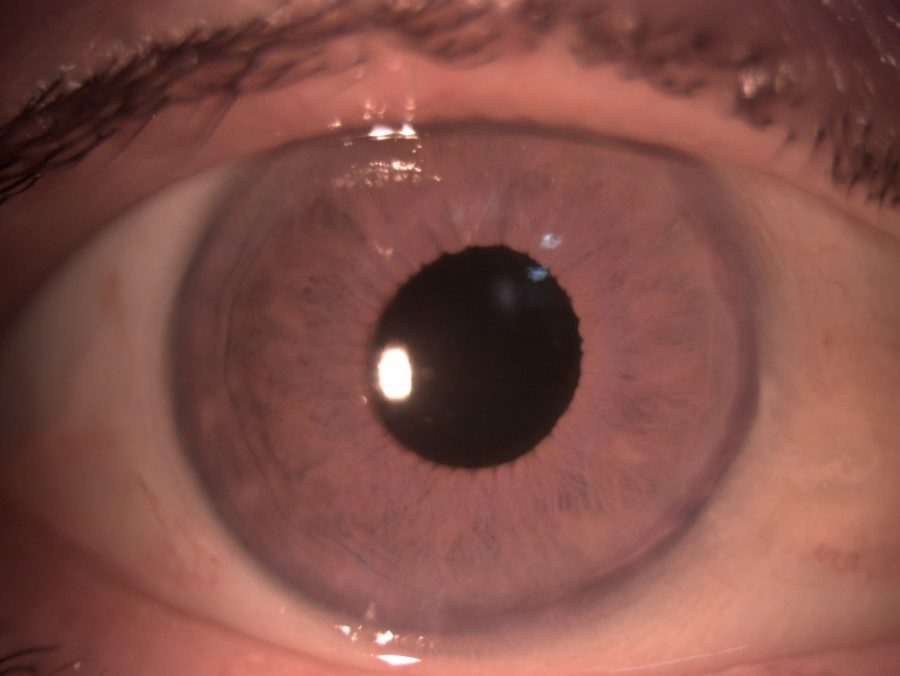

Figure 1: Color slit-lamp photograph of the right eye displaying pseudophakia and a slightly irregular pupil.

Case History

A 72-year-old Caucasian man was referred for intermittent blurred vision in the right eye (RE) over the course of several months, as well as long-standing floaters with periods of exacerbation. His clinical picture had been attributed to a recurrent hypertensive anterior uveitis of unknown cause which was being managed with the use of topical dexamethasone, tropicamide and a combination of timolol and dorzolamide.

The patient had undergone phacoemulsification with intraocular lens (IOL) implantation in the right eye 5 years before. His family history was unremarkable. On examination, his corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA) was 7/10 in both eyes (BE). Biomicroscopy revealed pseudophakia with a discrete irregularity of the pupillary roundness in the RE (Figure 1) and a moderate nuclear cataract in the left eye (LE). Both eyes had signs of pseudoexfoliation syndrome (PXE) and a moderate inflammatory anterior chamber reaction (cells+) was detected in the RE. There was no evidence of iris transillumination defects, nodules or keratic precipitates. Intraocular pressure was within normal limits in BE.

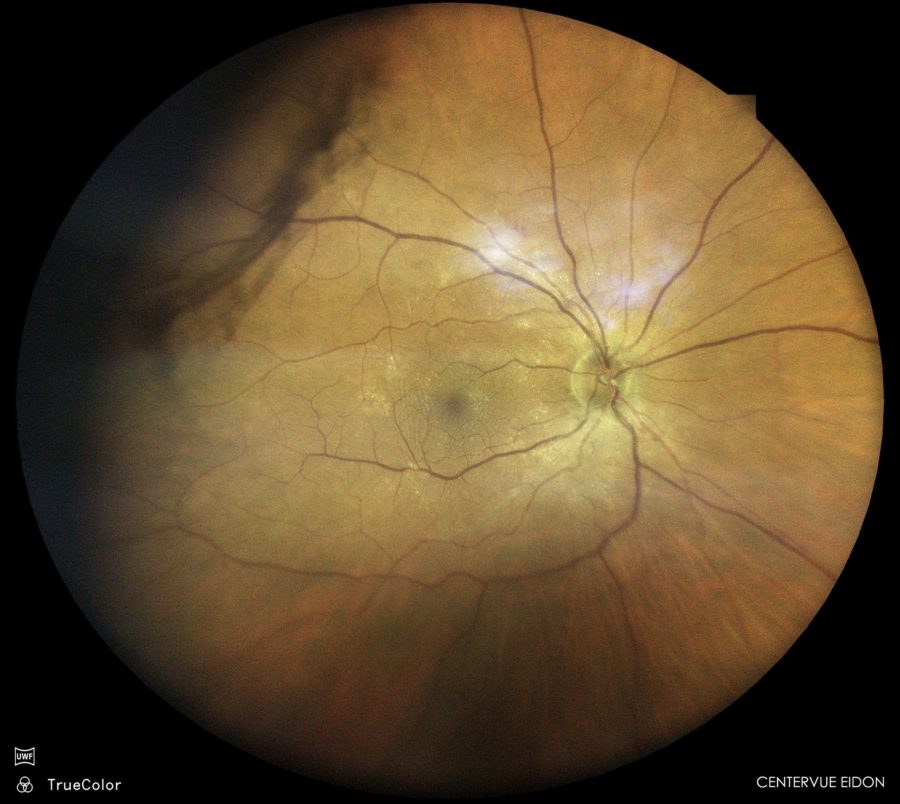

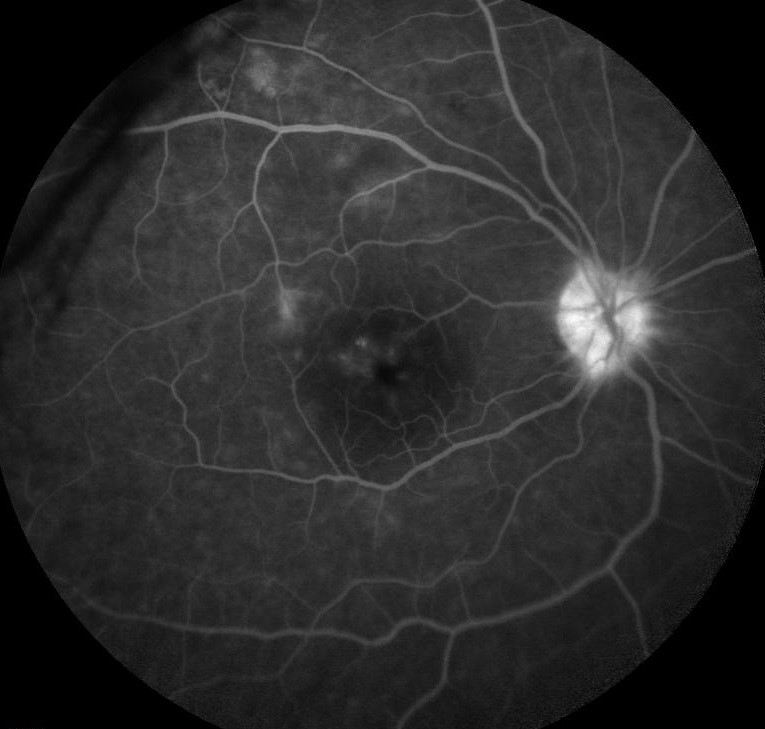

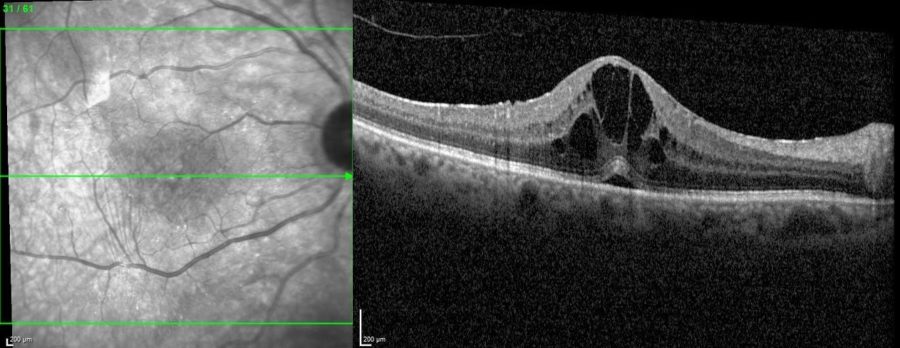

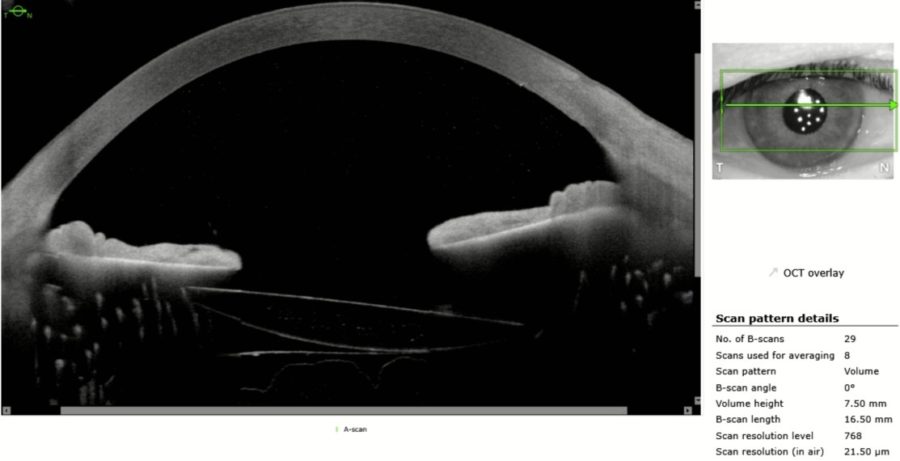

Fundoscopy revealed bilateral cellophane epiretinal membrane and a vitreous hemorrhage with an atypical location at the superotemporal quadrant of the RE (Figure 2). Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) showed a “hot disc” in the RE, with mild fluorescein leakage at the macula but without retinal vasculitis. (Figure 3). Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) confirmed the presence of cystoid macular edema (CME) in the RE (Figure 4). An anterior segment OCT (AS-OCT) was obtained, revealing a significant tilt of the IOL in relation to the pupillary plane, resulting in posterior iris touch and friction during normal iris excursion (Figure 5).

Figure 2: Color fundus photograph of the right eye (EIDON true-color confocal scanner®) showing a mild vitreous hemorrhage at the superotemporal retinal periphery.

Figure 3: FFA of the RE (Heidelberg Engineering®) demonstrating a “hot disc” and a focal leakage at the macula.

Figure 4: SD-OCT of the RE showing the presence of intraretinal fluid and cysts at the macula.

Figure 5: Anterior segment OCT (Heidelberg Engineering®) of the RE displaying a tilted IOL, resulting in posterior iris touch at the temporal side.

Differential Diagnosis

- trauma (e.g. blunt)

- hypertensive uveitis (e.g. herpetic)

- IOL subluxation due to underlying PXE syndrome

- proliferative retinal vascular occlusions (e.g. retinal vein occlusion, diabetic retinopathy, sickle cell disease)

- coagulation disorders

- uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema (UGH) Syndrome

The presence of iris chafing by the tilted IOL, in conjunction with hypertensive anterior uveitis and vitreous hemorrhage is consistent with the diagnosis of UGH syndrome.

Additional History

A full blood and imaging investigation was performed to exclude underlying infections and systemic inflammatory conditions, rendering negative results. Based on the clinical presentation and imaging findings, with a tilted IOL chafing the iris, along with a hypertensive anterior uveitis and vitreous hemorrhage, the diagnosis of uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema (UGH) Syndrome was established.

The patient was treated with topical steroid and non-steroid anti-inflammatory agents and topical antiglaucoma medication. Topical cyclopentolate was added to the drug regimen to reduce iris rubbing by the IOL.

Two months later, the CME and vitreous hemorrhage had resolved, IOP was within normal limits and there was no evidence of anterior chamber reaction. Tapering of dexamethasone and nepafenac was initiated. The antiglaucoma drops were discontinued but cyclopentolate was maintained.

The patient remains stable and there are no longer signs of active ocular inflammation. Due to the favorable outcome, no surgical intervention for IOL exchange has been planned for the moment.

Discussion and Literature

Uveitis glaucoma hyphema (UGH) or Ellingson syndrome is a relatively rare condition characterized by chronic inflammation, pigment dispersion, raised IOP, and intraocular hemorrhage in an eye that has undergone cataract surgery with IOL implantation. It is a late postoperative complication where the cause of inflammation is mechanical irritation to the iris and other intraocular structures due to chafing by the implants. It was first described in 1978 as related to rigid anterior chamber intraocular lens (ACIOL), but almost all anterior segment implants may be associated with UGH syndrome, including iris-sutured IOL, retropupillary iris-claw IOL, cosmetic iris implants, capsular tension rings, glaucoma filtration devices, scleral fixated lenses, IOL placed in the sulcus, and even the most modern single-piece posterior chamber IOL (PCIOL) placed in the bag.

IOL quality plays a significant role in the pathophysiology of UGH syndrome. Poor finishing of the edges (serrated, sharpened, or uneven), warped footplates, and imperfect polishing of injection-molded IOLs may all lead to recurrent mechanical excoriation of the iris, anterior chamber angle or ciliary body, hence disrupting the blood-aqueous barrier and leading to uveitis. Mechanical trauma to the iris by IOL optics or haptics induces the inflammatory cascade through complement and fibrin activation. Bacteria, leukocytes and red blood cells (RBCs) may adhere to the IOL surface, causing lens discoloration. A thick membrane of inflammatory debris (“cocoon”) may develop, totally or partially covering the optic, haptic or footplate of the IOL.

Patients with PXE have a higher risk of developing UGH syndrome, either by pseudophacodonesis due to the zonular laxity (resulting in chafing of the posterior iris surface), or by focal capsular fibrosis around the haptic causing iris touch. The rise in IOP may be caused by various factors, including hyphema, uveitis, pigment dispersion, direct damage to the anterior chamber angle, and steroid response to therapy. A high IOP at the first hemorrhage increases the risk for needing subsequent IOP-lowering therapy.

UGH syndrome may occur after uneventful ocular surgery or after an ocular surgery with intraoperative complications resulting in malposition of the implant. Patients usually present with multiple acute episodes of blurred vision weeks to months after surgery, in an intermittent white-out of vision or intermittent decreased vision fashion.

Gonioscopy can be valuable in the workup of UGH syndrome because it may disclose blood in the trabecular meshwork between attacks. However, the gold standard diagnostic modality for the condition is anterior segment imaging. It helps document the disease, monitor the response to therapy and counsel the patient. Anterior segment OCT and/or ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) may confirm the position of haptics and optics and their proximity to uveal tissue. B-Scan ultrasound is helpful in the diagnosis of cases presenting with vitreous hemorrhage. OCT of the macula can be used to detect CME. FFA helps to rule out the other causes of vitreous hemorrhage or iris new vessels. All the other causes of uveitis need to be ruled out. A coagulation profile and a history of anticoagulant medications should be sought in cases with recurrent hyphema.

The management of UGH Syndrome must be case-tailored, depending upon the cause. Antiglaucoma medications (topical and systemic if necessary) and corticosteroids are used to lower intraocular pressure and control anterior segment inflammation. Adjuvant therapy in the form of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cycloplegics is also helpful in relieving pain due to ciliary and iris sphincter spasm, bringing symptomatic relief to the patient and preventing IOL-iris friction. Miotics (including pilocarpine) should be avoided as they increase the mechanical chafing of the iris.

UGH syndrome is one of the most common indications (around 12%) of IOL exchange. IOL exchange is the definitive treatment but may not guarantee the resolution of UGH syndrome. IOL exchange, explant, repositioning, or amputation of IOL haptic should be performed if the inflammation is not controlled medically and the vision is reduced.

Keep in mind

- UGH syndrome must be considered in the differential diagnosis of recurrent uveitis in every eye submitted to cataract surgery with IOL implantation.

- Accurate diagnosis and prompt intervention in UGH episodes is essential to prevent long-term vision-threatening complications.

- Removal of the causative device is required in severe cases when unresponsive to clinical treatment.

References

- Sen S, Tripathy K. Uveitis Glaucoma Hyphema Syndrome. [Updated 2022 Mar 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK580530/

- Accorinti M, Saturno MC, Paroli MP, De Geronimo D & Gilardi M (2021). Uveitis-Glaucoma-Hyphema Syndrome: Clinical Features and Differential Diagnosis. Ocular immunology and inflammation, 1–6. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/09273948.2021.1881563

- Zemba M & Camburu G (2017). Uveitis-Glaucoma-Hyphaema Syndrome. General review. Romanian journal of ophthalmology, 61(1), 11–17. https://doi.org/10.22336/rjo.2017.3

- Armonaite L & Behndig A (2021). Seventy-one cases of uveitis-glaucoma-hyphaema syndrome. Acta ophthalmologica, 99(1), 69–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.14477

- Badakere SV, Senthil S, Turaga K & Garg P (2016). Uveitis-glaucoma-hyphaema syndrome with in-the-bag placement of intraocular lens. BMJ case reports, 2016, bcr2015213745. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2015-213745

- Lippera M, Nicolosi C, Vannozzi L, Bacherini D, Vicini G, Rizzo S, Virgili G & Giansanti F (2022). The role of anterior segment optical coherence tomography in uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema syndrome. European journal of ophthalmology, 32(4), 2211–2218. https://doi.org/10.1177/11206721211063738

- Alfaro-Juárez A Vital-Berral C, Sánchez-Vicente JL, Alfaro-Juárez A & Muñoz-Morales A (2015). Uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema syndrome associated with recurrent vitreous hemorrhage. Archivos de la Sociedad Espanola de Oftalmologia, 90(8), 392–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oftal.2014.11.007

- Zhang L, Hood CT, Vrabec JP, Cullen AL, Parrish EA & Moroi SE (2014). Mechanisms for in-the-bag uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema syndrome. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery, 40(3), 490–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2013.12.002

- Rajak SN, Bahra A, Aburn NS, Warden NJ & Mossman SS (2007). Recurrent anterior chamber hemorrhage from an intraocular lens simulating amaurosis fugax. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery, 33(8), 1492–1493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.04.018

- Cates CA & Newman DK (1998). Transient monocular visual loss due to uveitis-glaucoma-hyphaema (UGH) syndrome. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry, 65(1), 131–132. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.65.1.131

- Asaria RH, Salmon JF, Skinner AR, Ferguson DJ & McDonald B (1997). Electron microscopy findings on an intraocular lens in the uveitis, glaucoma, hyphaema syndrome. Eye (London, England), 11 (Pt 6), 827–829. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.1997.213

- Van Liefferinge T, Van Oye R & Kestelyn P (1994). Uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema syndrome: a late complication of posterior chamber lenses. Bulletin de la Société belge d’ophtalmologie, 252, 61–66.